The traditional approach to clinical trials involves lengthy, blinded randomized controlled trial formats with large study populations. The approved protocols describe the entire course of the trial, along with accepted endpoints. Much of this considerable effort ends in abandoned drug investigations due to high failure rates and exorbitant cost: up to 50% of late-stage trials are unsuccessful. These considerable constraints have tended to skew the industry towards investigating high-impact health issues that affect large populations, where potential promise of reward offsets the high financial risk of drug development.

.

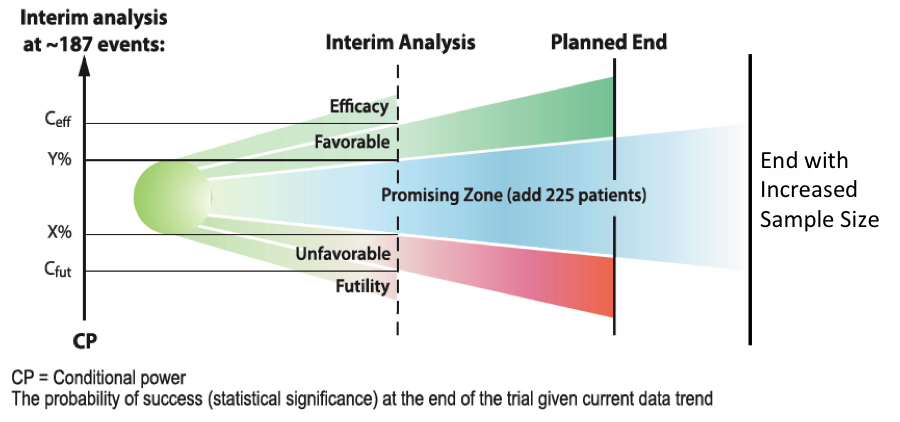

The mindset of the clinical trial approach has been undergoing change recently, with the gradual acceptance of the adaptive clinical trial. This innovative approach to clinical trial design encourages a nimble and evolutionary procedure that employs adaptive design to modify trial parameters as ongoing study observations accrue.

Modifications based on interim data may be implemented as the trial progresses, including fundamental parameters such as sample size, dosage, patient inclusion or transfer to a more appropriate arm of the study, dropping ineffective treatment groups or early abandonment of the investigation whether for success or failure.

.

Data generated is put to work immediately toward enhanced study direction, rather than be used in retrospective analysis at the study’s conclusion. Potential adaptations are set out prospectively and must not undermine the integrity or validity of the study.

.

Far from being a simple cost-cutting measure for industry, applying adaptive design to both exploratory and confirmatory trials has been actively encouraged at the federal level in the USA to promote higher success rates, to bring greater research attention to smaller health-needs populations, to address ethical concerns (by matching patients to appropriate trial investigations and by minimizing adverse effects), to spur faster creation of effective medications and also to maximize the development of this important industry and its economic impact.1

.

A major goal of adaptive clinical trials is to target and prioritize successful treatments for specific populations whenever possible. The use of validated biomarkers within this approach allows for increased specificity in the examination of sub-populations. A recent publication on breast cancer in the New England Journal of Medicine (the I-SPY 2 trial) examined different combinatorial therapies by tracking known biomarkers with an adaptive, agile approach: promising treatments were elevated in importance in this phase II study, while those without positive results were immediately dropped.2 Various drug candidates from multiple companies were evaluated in a single study arm, minimizing dead ends while maximizing efficiency and hastening the pathway toward new and effective treatments.

A major goal of adaptive clinical trials is to target and prioritize successful treatments for specific populations whenever possible. The use of validated biomarkers within this approach allows for increased specificity in the examination of sub-populations. A recent publication on breast cancer in the New England Journal of Medicine (the I-SPY 2 trial) examined different combinatorial therapies by tracking known biomarkers with an adaptive, agile approach: promising treatments were elevated in importance in this phase II study, while those without positive results were immediately dropped.2 Various drug candidates from multiple companies were evaluated in a single study arm, minimizing dead ends while maximizing efficiency and hastening the pathway toward new and effective treatments.

.

This increased flexibility brings hope for greater efficiencies, but also comes with caveats. Data may well be harder to interpret. The management of greater (and continually evolving) data complexity requires very advanced statistical modelling and oversight. The central role of the biostatistician takes on ever-more critical importance under shifting parameters and moving targets. Unscrupulous researchers may be tempted to use this data-driven complexity to cut corners, obfuscate and speed through the approval process. Not surprisingly, adaptive clinical trials are therefore more closely scrutinized. However, the enormous potential to reduce costs, streamline the clinical trial process and bring new drugs with positive and meaningful impact to market, including for previously under-prioritized populations, make adaptive design an enticing avenue for the future success of clinical trials.

.

- FDA: Critical Path Opportunities List. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/CriticalPathInitiative/CriticalPathOpportunitiesReports/UCM077258.pdf

- Park JW, Liu MC, Yee D, Yau C, van’t Veer LJ et al. Adaptive Randomization of Neratinib in Early Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:11-22.